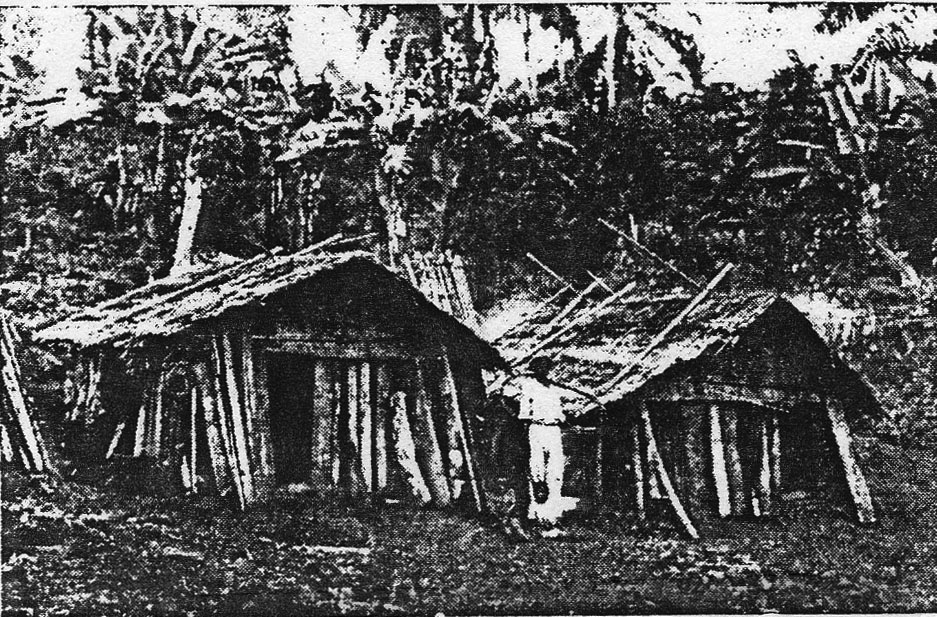

Bubi houses in Bariobe .

(From Los Bubis on Fernando Poo)

Chapters 10 and 11: Tattoos, customs

10. Bubi Tattoos

The Bubis used two forms of tattoo in the old days, one more recent than the other. According to stories from the eldest Bubis, the more recent form of tattoo has its origin in the times when vessels visited these African coasts looking for slaves. The objective of the barbaric and cruel Bubi tattoo was for a Bubi person, if captured and enslaved, to be able to recognize others from his country or tribe while he was in exile.

All who have visited this picturesque country know that the Bubi tattoo consists of carving or grooving the children’s faces in a most horrible way. In some, one sees shallow facial grooves, with very small, deep cuts. These are done in such a way that they are imperceptible from a distance, so the person is less disfigured. In others, quite to the contrary, there are deep grooves, wide and protruding, that make the person appear horribly disfigured and repugnant. I do not know where this difference comes from. It may be from the awkwardness of whoever did the cutting, or negligence in treatment, or from bleeding.

Back when this was the custom, it was usually performed on children three to five years old; however, I have seen nursing babies with facial grooves.

Before the operation, the child’s family consults with the spirit or morimó protector to see if he advises the child be tattooed. Ordinarily, the morimó responds affirmatively, but sometimes he answers negatively. That boy or girl is an exception to the general rule, by the express will of the morimó. Here we have the reason why, in the old days when the law was in full force, one would meet in the Bubi population some adult person with no facial cuts.

The children, generally, don’t know when they will be cut. They are carried away through deception to the house of the carver, for no one, voluntarily, lets himself be mutilated. Several of the adults in our missions have smooth faces, without cuts, because they suspected that they were going to be tattooed and escaped their family, taking refuge in the mission.

Once at the carver’s house, when the little boy or girl is amused and off-guard, he or she is subdued by two or three men, stretched out on the floor and tied up by the feet, hands, and waist to a stake, which had been prepared in advance. Thus he remains as if caught in a trap. The carver begins the operation with no regard to the victim’s screams and desperation. To carve the cheeks and jaws, he puts two fingers of his left hand in the mouth, in a way that he can’t be bitten by the desperate creature, then pushes them softly against the side and, with a very sharp knife, begins cutting with great care so as not to cut an important vein. The rest of the face, such as the forehead, the cheekbones, and the chin, are cut without difficulty.

The first cures were simply made with cool palm oil; others, with a pomade made of sifted ashes, a leaf mashed from a bush by the name bontola or bondola, water, and palm oil. They take great care that the wounds do not close, but that they heal open. This is how their faces appear plowed in big furrows, which, in thirty days, are usually entirely healed.

In times before ours, all regions of the island tattooed their children. He who writes this has seen many old men and, still, many more old women, with their faces plowed in big furrows in Baney, Rebola, Basilé, Basupú of the West, Balveri, and Batokopo. This cruel and savage custom disappeared in all regions of the island a few years ago. In the north, now, there are no young ones tattooed, and fewer old people, and in the south, while there are still old people and young people with the tattoos, one finds no carved children.

The other form of tattoo, much more ancient among the Bubi, consists of taking the point of a knife or another sharp instrument and making flowers, branches, and other figures in different parts of the body, mainly in the arms, chest, and back. These tattoos beautifully adorn the body. No coloring substance is put in these tiny wounds, as is done in other African tribes. Generally, only the young women had them, though on rare occasion a man would tattoo himself. In the present day, as all Bubis dress decently, this custom has disappeared.

In the old days, they would pierce their ears in an extraordinary manner. In the holes, they would put toothpicks, hollow clay piping, metal rings, and enormous earrings made of strings of chibo or shellfish. This customs was common among men and women, but, in these days, is no longer in use because all strive to imitate European fashion.

Whoever has seen the Bubis half-dressed may have observed knife cuts of various sizes in the style of their faces on other parts of their bodies. Such cuts are not part of their tattoos. They were made to open some tumor, to free some acute rheumatism, or to cure a sickness that appears to be their own and peculiar to them, called bajaba, majama, mahama, and in English is translated “illness of grease or fat.” When the incision or cut is vertical on the head or forehead, it proves that it was a bloodletting. The Bubi, in order to set free a migraine or sharp pain in the head, practices blood-letting on top of the forehead. Small cuts seen around the neck are evidence that a scrofula or other small tumor was extracted, which the Bubis believe are the main cause of sleeping sickness. To take precautions from such a frightful ailment, they extract the tumors by means of a boring tool made from palm or bamboo. Those tumors they call bichikó biotoló, which is, “sleeping glands.”

11. Bubi Customs

The customs of the Bubis were, in times long past, barbaric, savage, and cruel. In a book written by a German merchant from the Gold Coast, translated into English and printed in London in 1703, one reads this text: “The island of Fernando Poo is inhabited by a savage and cruel sort of people,” in such manner that no one dared dock at those beaches. And, a Portuguese memoir dealing with the inhabitants of Fernando Poo tells that, in the year 1810, an English boat moored in the Bay of San Carlos to replenish its fresh water from its springs. In arriving in a row-boat on the beach, they came upon a patrol of entirely nude Bubis armed with darts called bechika or mechicha.

Throwing them at the mariners in the rowboat, they killed them all. This is how foreigners developed such fear of the island.

The clear proof of their old barbaric customs lies in the continuous and bloody wars between some districts, some towns in the same district, some families, and the never-ending private vengeances. One often hears that the old Batetes, in the woods of Boloko where today one finds the property of Vivour (1) in San Carlos, preferred this site to ambush the Baloketos. There, in the not-too-distant past, they executed cruelties in most horrific scenes. Hiding in the thickets, the Batetes waited for the Baloketo to come down to the beach, where they would spring from their hiding places and attack the defenseless Baloketos, killing the male adults and carrying away women and children. Surprise attacks on travelers and treacherous murders were a common thing, so much so that for a chief to gain more power and influence, to be able to have the title boana or boabí, equivalent to our “hero” or “illustrious man,” he had to kill a personal enemy or an enemy of the tribe. There was a condition attached that the homicide involve stealth and deception.

The villages of western Boloko, Moeri, and Risule, which were larger in male population than female, once in the past asked for virgins from the Basakatos. They refused. Angry, the Baeris and Basules began cruel and incessant harassment of the Basakatos. The Basakatos, considering the superior numbers of their opponents, avoided them, shrinking from combat and patiently suffering their abuses. But the insults, assaults, and insolence of the Baloketos came to such an extreme that the Basakatos accepted the challenge. Both sides met on a plain high above the path off the old road to San Carlos. The Basakatos fought in desperation, determined to conquer or to die. They attacked with such ferocious courage that they broke the enemy’s ranks, throwing them into confusion. But soon the enemy was rallying. That innumerable multitude of Baeri and Basules fell upon the Basakatos, decimating their army. There was such carnage that the plain was literally filled with bodies. With this, the Basakatos were forced to surrender and beg for peace. The Baloketos granted this with two conditions: first, the surrender of the land included between the rivers Balóhó and Rupé. We Spanish call the river Balóhó or Malóhó the Rio Grande, and others, who seek to English-ize all, give it the name Big River. Second, the Basakatos were required to pay an annual tribute of virgins of marriageable age. To such great humiliation were the Basakatos subjected. In the various visits I made in 1897 from the Musola mission to the villages of Risule and Moeri I investigated the truth of what I have just told.

There once was in Bokoko two girls who were a wonder of perfection and beauty. The main mochuku of the Batetes, named Mai, was in love with them and asked their family for them. However, as Mai was a declared enemy of the Bokokos, the family refused to give them up. Mai, in a rage, swore to avenge himself and to seize the beauties by force. He called together his most loyal subjects, armed them, and went to the outskirts of the village where the girls lived. This happened in the field-working season. The Bokokos, off-guard and unaware of what was about to happen, went about their daily work, leaving at home little ones under the care of the old women and mothers with nursing babies. They also left at home the aforementioned girls, who were so beautiful and graceful they never worked in the fields, as they might mar their extraordinary beauty.

Later, when the other people went to the yam fields, the Batetes came out for the ambush. They easily seized the virgins and carried them away to the rijata or ritaka of Mai, making a great show of their victory.

The Batetes were so prosperous in their raid that they decided to repeat it. This second double-turn ended in one of the great misfortunes recorded in Bubi history. This time while the Batetes took the road to the mountain, the news came to the Bokokos that the Batetes were returning. The Bokokos armed themselves and hid in the dense jungle on both sides of a ravine where the Batetes must cross. When the Batetes were in the depths of that ravine, quite confident and secure in their plans, they found themselves caught between two fires, as we might say, unable to defend themselves or to escape on either side. The Bokokos were merciless to the Batetes. In the massacre of that terrible day, the mochuku Mai himself was destroyed.

Even with Mai’s death the fights and wars between the two villages continued. There was no peace until the Bacha, more brave and skilled in warfare than the Batetes, rushed beyond the Ndaha River to take possession of Bokoko terrain encompassed between the Okó and Ndaha rivers. The Bacha abandoned their old homeland, which was east of Ríobanda, and settled in the place occupied by the Bokokos.

The Bacha are, as I said, better fighters than the Batetes, and were nicknamed bualatokolo by Vivour, which means “brave and fierce troop.”

This state of perpetual island wars lasted a long time, until the supreme mochuku of Biapa, named Moka, whose dominion extended across all boundaries of the island, gave an edict prohibiting any village or individual from taking self-justice. He threatened severe penalties to those who did not comply. Moka considered that if these private wars continued, the extermination of the Bubi race would be swift and certain. All were required to bring their complaints to his tribunal. To this end, he instituted a body of swift troops charged with punishing those villages and districts that were rebellious of his edicts. They called this troop the Lohúa or Lojúa. At the end of 1888, Reverend Father Jaime Pinosa, Superior of the Mission of María Cristina, impeded the execution of the sentence dictated by Moka that the chief of Ruiché de Balacha, by the name of Mohale, be decapitated. Moka had great veneration and respect for the missionaries. The last foray of the Lojúa for the population of San Carlos Bay took place in January 1895. Rev. Father Sala, Superior of Batete, communicated immediately to Governor General José Puente that squads of the Lojúa were on patrol. The esteemed José sent a body of armed sailors in their pursuit. The Lojúa escaped to the heights of Biapa. Since then, the Lojúa has made no more forays. The great mochuku Moka died in March 1899 and with his death, so died the Lojúa. Fathers Pardina and Abad were present at the death of Moka, but they did not see him.

(1) Guillermo Vivour, an early island settler. -- Trans.